A notable visual that has developed during the COVID-19 pandemic is the huge queue of ships on the horizon, stretching from the Port of Long Beach (POLB) all the way down to Huntington Beach. A plethora of vessels is anchored offshore, including mighty tankers that weigh four times as much as the Queen Mary, and cargo ships a quarter-mile long that can hold 20,000 shipping containers. Although unprecedented, this volume of incoming ship traffic is being handled safely and efficiently by several agencies which have been working in the Port together for decades.

The pandemic caused a chain of events that led to this extraordinary cargo surge. Noel Hacegaba, Deputy Executive Director of POLB, explained: “In 2020, we went from ‘doom and gloom’ to ‘fast and furious’ on the turn of a dime. When the pandemic hit Asia, manufacturing in China — our largest trade partner — was shut down. Then, when manufacturing resumed in spring, we [USA] were on lockdown. Spending shifted from services to goods; We were at home, ordering a lot of product. So the combination of limited supply from China, growing demand in the U.S., and a Port workforce weakened by COVID-19 created the cargo surge and the ship traffic jam we’re seeing now.”

Ships arriving at the Port of Long Beach are organized by the Marine Exchange of Southern California, which runs the Vessel Traffic Service outside the breakwater. A non-profit which has been servicing all Southern California harbors since 1923, the Marine Exchange serves as a sort of “air traffic control” for incoming ships, assigning anchorages, taking ship size and water depth into account, and providing minute-by-minute updates to the Port, longshoremen, and Jacobsen Pilot Service, which has had an exclusive contract with the City of Long Beach to pilot incoming ships inside the breakwater since 1924.

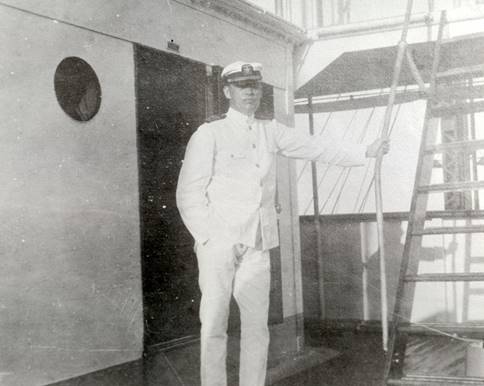

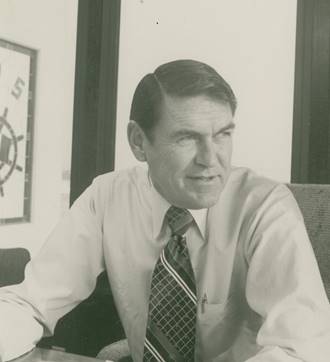

“We have never shut down — even for an hour — since 1924,” said Tom Jacobsen, President and CEO of the company founded by his Grandfather, Captain Jacob Jacobsen. Back then, the Port area was mostly mud flats, there were only a couple of docks, and incoming cargo was mainly lumber brought from Oregon and Washington by steamships to fuel the Los Angeles and Long Beach building booms.

Business picked up for Jacobsen during World War II, when the company was subcontracted by the Navy to pilot its vessels. After a post-war lull, the global commerce boom ensured that the Ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles would remain busy. Together, the Ports now handle 40% of the USA’s incoming goods.

It is mandatory that ships entering the Port of Long Beach be manned by one of Jacobsen’s 20 pilots, who are all trained and qualified to handle any arrival, from private yachts to massive cargo ships, cruise ships, and tankers. When a ship is ready to enter the harbor, a Jacobsen boat takes the pilot a few miles out to the ship, where a rope ladder is lowered and he climbs aboard. “It’s like valet parking,” said Jacobsen. “We take the ships in and out.”

The Jacobsen control room provides a complete panorama of the harbor and is equipped with state-of-the-art radar which enables pilots to move safely even during thick fog.

“Not a day goes by that I don’t enjoy the view,” said dispatcher Rob Tinsley.

Pilots take their own GPS guidance systems onboard, ensuring that there will be no mistakes. But even with all the high-tech gear and communication, ships are still affected by basic forces of nature. For instance, a 15-mph wind generates 80 tons of force on the side of a massive cargo ship, which the pilot and three or four tugboat captains must contend with.

The tide is a huge factor as well; To pilot a ship under the Gerald Desmond Bridge and into the harbor’s back channel, the low tide window must be precisely calculated to assure safe clearance. The largest container ships clear the bridge by just three feet (see photo). The new bridge, 50 feet taller, will eliminate this problem.

Jacobsen is patched in with Port Security and with the Coast Guard, which provides the law enforcement arm of harbor safety. These agencies, along with the Marine Exchange, work together to provide seamless ship flow in the Port, no matter what challenges face them.

“The Port is one of the region’s largest economic engines,” said Hacegaba. “We generate one out of five jobs in Long Beach, and over half a million in Southern California. With the Port in close proximity to our Downtown area, there’s no question that it will play a vital role in the economic recovery of our region and our nation. The fact that we’re busy bodes well for our city and our region.”